.png)

Seeking private investment is one of the most decisive milestones in a startup's journey. It allows you to accelerate growth, professionalize the team, consolidate technology and position yourself against competitors.

However, it's not always the right step or it comes at the right time.

Raising external capital without a clear plan or at a stage that is too early can have counterproductive effects: loss of control, excessive dilution or even the blocking of future rounds.

Over the past few years, the professionalization of the Spanish entrepreneurial ecosystem has generated a change in mentality: founders are increasingly seeking to understand why and why to raise investment, regardless of numbers or valuation.

In this article, we explore when it makes sense to seek private investment, how to define the optimal amount to raise and what criteria to follow to do so in a strategic and sustainable way.

Private investment as a tool, not as an end

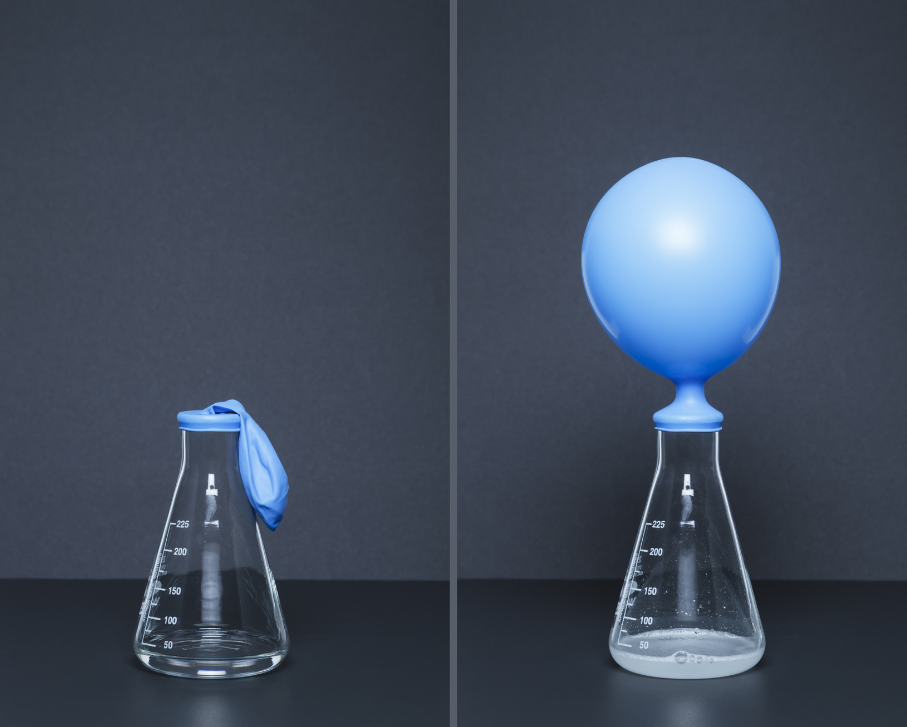

One of the most common mistakes in the early stages is to consider private investment as the starting point of the project, rather than a tool to accelerate what is already working. The financing of an investor, whether a business angel, fund or corporate venture, should come when the business model begins to validate its traction and the additional capital allows for multiplying the results, not creating them from scratch.

Money, in this context, must have a clear and measurable destination: expanding a validated product, opening a new market, scaling up a commercial team or consolidating the technological base. Seeking investment without an operational plan that translates capital into specific milestones often leads to tensions with partners, unmet objectives and difficulties in justifying new rounds.

Therefore, before opening a round, it is essential identify what milestones you want to achieve with that capital and what evidence exists that investment will make it possible to achieve them. If the objective is still to validate the market or build the MVP, it may make more sense to opt for non-dilutive public funding (such as ENISA, CDTI or regional programs) or to self-finance through the first sales.

When does it make sense to seek private investment?

The answer depends on three main factors: the degree of validation of the business model, the scalability of the product, and the timing of the market. In practical terms, raising private capital makes sense when:

- The product or service is already on the market and has initial adoption or revenue metrics.

- It has been demonstrated a Product-Market Fit incipient or at least a strong Problem Solution Fit.

- There is a clear growth strategy that justifies the efficient use of capital.

- The corporate structure is organized and the founding team is aligned in vision and commitment.

When these elements are in place, private investment becomes a natural accelerator of growth, not a path to survival.

Investment phases and objectives in each one

Not all rounds are the same or serve the same purposes. The need and size of the investment vary depending on the company's maturity phase.

Pre-Seed: Validate the opportunity

In this phase, the priority is to confirm that the problem exists and that there is enough market to solve it. Investments are usually small (from 50,000 to 250,000 euros) and come from the founders themselves, Friends, Family & Fools or business angels with a high risk appetite.

More and more specialized early-stage funds (such as Draper B1, Kfund Seed or Lanzadera) are participating in these stages, especially if the team shows previous experience or differential technology. However, raising too much money before validating the model can be dangerous: it increases dilution and creates expectations that are difficult to meet.

Seed: test the model and demonstrate traction

La Ronda Seed marks the time to turn the product into a business. Here the investment is used to acquire customers, improve the product and test unit economics. In Spain, seed rounds are normally between 200,000 and 1 million euros, with pre-money valuations of 1 to 4 million.

Investors expect to see month-to-month growth, early revenue metrics and a solid expansion plan. The objective is not immediate profitability, but rather the validation of the scaling model.

Series A: Scale Efficiently

Once the model is proven to work, the expansion phase comes. Institutional funds are looking for companies with stable MRR, sustained growth and a team capable of executing on a large scale. The Series A rounds range from 1 to 5 million euros, with dilutions of 20-25%.

At this stage, raising private investment makes sense when capital will make it possible to multiply existing results: expanding internationally, diversifying products or professionalizing the structure.

In short, the optimal time to seek private investment is when the startup can demonstrate a clear relationship between capital and measurable growth, ideally with data to support its efficiency and return potential.

How to calculate how much capital to raise

Determining how much money to raise is not an intuitive decision, but a strategic one. It should be based on three pillars: operational needs, time horizon and milestone planning.

The first step is to define what milestones the company wants to achieve in the next 18-24 months (for example, doubling revenues, opening international markets, or achieving operational break-even). The costs associated with those objectives, including equipment, technology, marketing, infrastructure, etc., are then quantified and a safety margin of 10-20% is added.

That final figure represents the minimum amount of the round. However, before confirming it, we must analyze how it will affect the dilution. For example, if a startup is valued at 2 million euros pre-money and receives €500,000 in investment, the transferred share is calculated as:

This means that the founders would keep 80% of the capital after the round. If the company raised 1 million with the same valuation, the dilution would be 33%. For this reason, raising more money than necessary can be counterproductive, especially if all of the growth milestones have not yet been validated.

Most investors recommend planning each round to cover between 18 and 24 runway months, enough time to reach a tipping point that justifies the next phase of funding or operating profitability.

How much is too much (or too little)

Raising too little can leave the company unable to execute and force new hasty rounds, causing fatigue among investors and founders. On the contrary, lifting too much creates pressure to grow faster than the structure allows and can inflate unsustainable valuations.

In general, a round should allow objectives to be achieved without compromising control or increasing operational risks. Investors tend to prefer prudent and realistic founders in their projections, who demonstrate capital efficiency and a clear connection between spending and results.

A common mistake in early-stage startups is to define the amount based on the “money that could be spent” instead of the “money that is needed to grow”. The investment must be aligned with a realistic roadmap, where every euro has a purpose and an expected return.

How to decide who to raise capital with

Just as important as knowing when and how much to lift is deciding who to do it with. The investor profile directly influences the evolution of the company. Not all investors provide the same type of value: some offer strategic support, others access to the market, others simply capital.

Business angels are especially valuable in the early stages because they provide operational knowledge, network of contacts and flexibility in negotiations. Venture capital funds provide financial discipline, structure and monitoring capacity, but they often require stronger metrics and reporting commitments.

Selecting the right partner involves understanding their Track Record, your investment thesis and your level of involvement. A misaligned investor can be just as damaging as a poor valuation. Ideally, the relationship with the investor should be based on trust, transparency and a shared vision of growth.

Avoid the most common mistakes when looking for investment

The most common errors in fundraising processes tend to be repeated among startups in all sectors. The first is to seek investment too soon, before having a validated product or a clear message. Without adoption metrics or a tangible business model, convincing professional investors is extremely difficult.

The second is to set a disproportionate assessment. An inflated figure may seem attractive, but it tends to complicate future rounds and alienate strategic investors. On the contrary, a valuation that is too low erodes trust and can lead to internal conflicts due to excessive dilution.

It's also common to neglect the financial narrative. Investors don't just buy data, but vision, consistency and ability to execute. Showing realistic projections, achievable milestones and clarity about the use of capital conveys professionalism and increases trust.

Finally, many startups forget to combine private investment with complementary public funding, allowing runway to be expanded and dilution reduced. Programs such as ENISA, CDTI or regional lines can represent up to 30-40% of the funding plan without giving up equity.

When not to raise private investment

Not all startups need to raise external capital at the same stages or for the same reasons. The need, or not, for investment depends profoundly on the business model, the product development cycle and the cost structure.

In models such as B2B SaaS, marketplaces or digital businesses with short validation cycles, it can be counterproductive to raise investment too soon. If the product is not yet validated, if there are no clear signs of traction or if growth can be financed with clients, grants or own resources, incorporating private investment can generate pressures and expectations that the project cannot yet sustain.

However, this does not apply equally to all sectors. In areas such as health, biotechnology, hardware, deep tech or medtech, early investment is often essential. These models require long R&D cycles, highly specialized teams and, in many cases, regulatory processes before generating revenue. For these types of companies, raising capital, and not a little, before reaching the market is not an option, but rather a structural requirement.

Therefore, rather than talking about “to lift or not to lift”, the key question is: What does your model really need to move forward in a healthy and sustainable way?

Forcing a round for image reasons, a comparison with competitors or a market trend is a common mistake. Each startup has its own pace, and moving ahead with a round without solid foundations can compromise both the strategy and the credibility of the project.

Conclusion: private investment with purpose and strategy

Private investment is a powerful lever, but not a starting point. It makes sense when there is a solid foundation, a validated product, consistent metrics, a committed team, and when capital translates into measurable growth.

Determining how much to lift and with whom to do it are strategic decisions that define the company's trajectory for years. Therefore, beyond the figure, the focus must be on maximizing the impact of capital, minimizing dilution and maintaining alignment between founders and investors.

Ultimately, raising meaningful investment means doing it at the right time, with partners who provide value beyond money, and with a clear vision of how each round builds the company's future.